Escuela de Arquitectura y Estudios Urbanos, UTDT

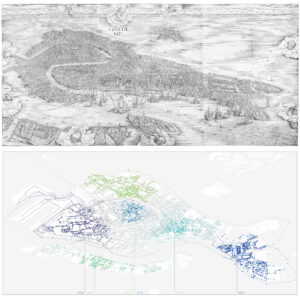

Above: ‘View of Venice, 1500.’ Jacopo de’ Barbari. Source: collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Google Arts & Culture

Below : Spectral Clustering of Venice. Trevor Ryan Patt, 2020. Geodata source: Piano di Assetto del Territorio, Comune di Venezia, accessed 27/04/2018.

Précisions & Projections, Fall 2020

Thinking Cartographically, Fall 2021

Abstract

The making of maps is an operation both critical and projective. This course will examine the map and mapping as an object or action “that fosters connections between fields… open and connectable in all of its dimensions.”¹ We will look at the evolution of maps, the unique representational techniques of cartography, architectural and artistic practices that are based in mapping, and the impact of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) on the relationship of designers to cartographic questions.

In addition to discussion of the role of maps historically, the course will introduce computational methods of analysis that can be used to identify patterns within geospatial data. Students will produce a series of maps throughout the term and explore the connections from mapping to design practice.

Objetivos

The course will illuminate many of the potential applications of mapping for architectural design practice. As such, it is not strictly interested in developing a technical facility with, for example, GIS software but rather in developing conceptual approaches that can connect architectural and urban design to the scale of geospatial data. The course will emphasize the development of a critical sensibility that is familiar with foundations of cartographic thinking and representational structures in addition to techniques for making use of raw geodata.

Fundamentación teórica

“As a creative practice, mapping precipitates its most productive effects through a finding that is also a founding; its agency lies in neither reproduction nor imposition but rather in uncovering realities previously unseen or unimagined, even across seemingly exhausted grounds. Thus, mapping unfolds potential; it re-makes territory over and over again, each time with new and diverse consequences.”²

James Corner’s characterization of the creative content of mapping forms the central understanding of the course’s approach to the relationship of mapping to design practice. At the same time, trends in cartography are characterized by two contrasting progressions. The first is an ever-increasing resolution of fidelity. This is the domain of GIS and GPS navigation systems, of geospatial data and satellite photography. This direction can be summarized by what Michel de Certeau’s describes as the ‘scopic drive,’ the technocratic view that planners operate from but also an acorporal and detached view.³ The second tendency is an increase in locality and embeddedness, which aligns rather with the ‘myopic view’ of de Certeau’s pedestrians. Aligned to this position are the sensors and servos of the emerging smart city, subjective mappings, but also the positional location of mobile map apps, centered on the user’s location.

The tension between these poles is the main axis of exploration in this course. Ultimately, these two tendencies are not opposed but inseparable. Borges’ fable on the ‘Exactitude in Science’ illustrates how the extreme terminus of fidelity results in completely sacrificing the synoptic dimension to the point that the map can then only be accessed or read myopically.⁴

Contenidos

The course will introduce historical material through lectures and assigned readings. As the design production will rely on digital geodata and computational techniques for translating, processing, and analyzing said data, technical tutorials will be also be offered most weeks.

Metodología

The course will address different themes related to cartography or cartographic techniques on a weekly basis: codification, overlay, topography, psychogeography, topology, semiology (and asemic representation), manipulation and distortion, praxis, infinity, etc…

Instruction will be a mixture of lecture, discussion, and the production of maps and a mapping-based design outputs. The creative work will necessarily involve diverse methods but will largely be focused on the use of familiar, architectural 3d modeling software (i.e Rhino and Grasshopper). See following section, Operatividad, for more detail.

Operatividad

Following the earlier interpretation of the link that Borges establishes between the synoptic and myopic poles of cartography, it may also be possible to reinterpret Le Corbusier’s reaction to the aerial view of the South American landscape that he documented in Précisions.⁵ Typically, this moment in architectural history falls firmly on the side of the scopic—the ability to resolve an entire territory into a single image and impose a visual logic onto it—but these projects also propose an architectural form meant to be occupied and therefore seen not all-at-once.⁶ In limited views, these land-form buildings operate as instruments that map a localized moment of the territory (the topography, for example in São Paolo). This is how some land art, like Richard Serra’s Shift, have been described, revealing “the ‘capacities’ of the site, while magnifying their variety and singularity… while walking within the sculpture.”⁷

Using the four sites identified by Le Corbusier as featured in Précisions (Buenos Aires, Montevideo, São Paolo, Rio de Janiero), students will complete a series of mapping exercises related to the weekly themes of discussion. These exercises will have two parts: first, a graphic presentation of a particular dataset in two dimensions; and second, a projection of this spatial data into an architectural or urban form that localizes or indexes that information in a legible way. The graphical studies will be collated in an atlas, while the formal studies will be superimposed over the existing urban form and will continue to aggregate throughout the term resulting in a new indexical urbanism. In both sets of work attention to clear and precise visual communication is needed.

The precise methods, operations, and calendar varied between the two semester offerings, with the first being more incremental and the second more integrated and with a stronger emphasis on aerial vision and the reformulation of Corbusier’s project. This was facilitated by limiting focus to the two Brazilian cities and the similarities of their situations.

In the first iteration, the semester concluded on the construction of a Non-Site interpretation of the semester’s work; in the second, the project was translated into an interactive ‘Mapbox Scrollytelling’ webpage.

Footnotes:

1: Gilles Delueze and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus. Translated by Brian Massumi. University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

2: James Corner. 2014. ‘The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique, and Invention.’ in The Landscape Imagination: Collected Essay of James Corner 1990-2010. Princeton Architecture Press.

3: Michel de Certeau. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven F. Rendall. University of California Press.

4: Jorge Luis Borges, J. L. 1998. ‘On exactitude in science.’ in, Jorge Luis Borges, Collected Fictions. Translated by Andrew Hurley. Penguin Books, p325.

5: Le Corbusier. 1991. Precisions on the present state of architecture and city planning. MIT Press.

6: Further context in: M. Christine Boyer. 2003. ‘Aviation and the Aerial View: Le Corbusier’s spatial transformation in the 1930s and 1940s.’ in diacritics, 33.3-4 Fall-Winter, p 93-116

Adnan Morshed. 2002. ‘The Cultural Politics of Aerial Vision: Le Corbusier in Brazil (1929).’ in JAE, v55n4 May, p201-210

Ramón Pico. 2016. ‘The planetary garden. Where natural and human intertwine.’ in JAU, v42n3, p70-79

7: Yves-Alain Bois and John Shepley. 1984. ‘A Picturesque Stroll around Clara-Clara.’ in October, v29 Summer, p32-62.